Abelard and I

***

So Abelard has finally captured me, keeps me chained to loop screwed into a wall in his basement, but it won’t be for long. I’ll escape, if I want to. But the question is, do I want to? Soon he’ll be here, will come creaking down the creepy stairs with that wheezy breath of his (Abelard is so out of shape) and will attend to the torture device. Is it his, or is it mine? It’s both of ours.

Chained here, I’ve been sleeping better of late, have discovered the comfort in this. But last night I dreamed that I was running through a dark alley, that I was being pursued, and that I was slowed by a canvas sack dragging along behind me. I could hear it scraping. It was attached by an umbilical, and it wasn’t just a sack, because there was someone in it, but I didn’t want to look.

Here comes Abelard.

The first time we met, Abelard and I, I was seven. He invited himself for dinner, came in a suit and tie, and my mother made a roast. My father talked about unions and baseball but Abelard, he didn’t say much, because Abelard has never said much. He watched me the whole time, and afterwards we went to the TV room, down in the basement, just Abelard and I, and I sat on his lap. I remember him staring at me, nodding his head slowly and sometimes laughing just a little at the antics on the screen. They say these first meetings are important. They say a bonding takes place.

Twice more that year he would come to our home; once on my eighth birthday, where he stared in the bay window, and then one evening while I was in the bathtub. My mother came in and said Mr. Abelard is here and he wishes to wash you hair. And that’s what Mr. Abelard proceeded to do.

Abelard clicks the light at the bottom of the stairs and comes to me, checks the chain, never looks me in the eye. I rattle my chain and make choking noises, and he turns for a moment, seems to consider something, and then turns away. Not very impressed, that’s how I read that expression of his. I’m up to my old tricks. He moves farther into the basement and clicks on more lights, considers the torture device, considers me, and I consider all this just a bit boring. I ask him if we’ll be having breakfast this morning. Eggs? Sausage? Golden heaps of scones? There’s a paper bag on a toolbox behind him, and he brings it to me.

It wasn’t until two years later, when he visited me at school that Abelard and I met again. He knocked on the classroom door and the teacher, Mrs. Hardaway, had to point me out, though me, I recognised Abelard right away. His narrow head, his round little glasses. His stiff spine. He was allowed to sit at a desk next to mine, watched me while I wrote down the names of all the planets in our solar system and their order of distance from the sun. Stuck, I even asked Abelard if Neptune was farther than Uranus, or vice versa, but he only lifted his eyes and stared out the window, as if he could see.

Yeah, that’s Abelard.

First he gets out the spray, then the cloth, then he cleans the device’s precious Plexiglas, slowly walking the length of the worktable, spraying and polishing while I eat a stale doughnut dunked in water that tastes of chlorine. I tell Abelard that it’s looking good, ask when will it be ready? I laud the genius of his invention, saying it is so sui generis, and he grunts and nods. Then I tell him I have to go shit and he undoes the chain from the wall and takes me to the dank basement washroom, no bigger than a closet. Not sure why, but I’m feeling extra talkative this morning.

On the toilet, staring at the door (I know he’s on the other side doing the same — though not on the toilet), I ask him if he remembers what I wore for my high school prom. In a distracted voice he says something, literally “something.” Wiping, I tell him that I thought he was going to do it that night, seeing that I was no longer under the aegis of the public school system. You were there at my prom, and I was sort of proud, I tell him. Flushing, I say, Oh Abelard, whatever are we going to do?

No answer, though two days ago he told me to shut up, first sign of anything rude from Abelard. I want to ask him again why he picked me, and why he waited three years after high school, and what are his plans after me? But something tells me he’s too single-minded to have thought ahead. He won’t answer, and it’s time for a tour of the device.

First of all, it’s long. Maybe twenty feet long. Secondly, lying flat on the worktable, its shape is that of a guitar. Towards where the body becomes the neck there is what I call the “Cockpit” with various leather straps to hold me down (this, probably, is the least inventive thing about it, but I guess all wheels should be round). And, thirdly, its interior is full of metal rods and circuits, gears and snapping traps. All nicely polished. Does he intend to strap me in and let mice run loose, or rats, yet he’s so intent on capture and torture that he can’t even let them be free? The Plexiglas walls are about a foot high, and are sealed at the bottom joins. Does he intend to fill it with water, turn on a switch and electrocute me? Electrocute me while I’m drowning? And thus taking all the twitching rats and mice with me? (We’ll be buried together, and that’ll be one strange open coffin.) What are you up to, Abelard? Obviously, you’ve had too many years think about this.

Abelard, I say, you are a mad genius.

So Abelard was at my prom, and one afternoon a week later Abelard trailed me and my driving instructor for a few miles (how I wanted to floor it!), and then Abelard disappeared for over a year. I enrolled in college. Then came one evening, or night (it’s a little foggy) where we were all drinking, praising the end of our mid-terms, and there was Abelard, at the end of the table, sipping a beer, raising his glass to me. The table became silent, and Abelard left, his beer half full.

It was then that I first thought about Abelard, wondered about his life beyond his visitations with me. That he didn’t have a family seemed obvious, but what did he do in his spare time? Did he have a job, or a hobby? A lover? Had he taken on more than me? I began fantasising about my inevitable capture, which everyone says is normal, and also inevitable, even the sexual arousal that accompanies it. My indifference towards Abelard ended that day, and I began to leave my door unlocked at night, began sleeping in the nude and taking long showers with the door open (or, when on campus, finding hours when the showers were deserted). I see now how it all was a cliched collegiate flirtation with annihilation, and at least I didn’t start wearing black all of the time.

Abelard begins to hum to himself. He has a beautiful voice, rather high and tremulous, like you’d never expect. It’s much too early in the morning for anything really, and he didn’t bring me coffee, so I decide to fall asleep. I’m going to sleep for a spell, OK Abelard, so don’t make too much noise. But do keep humming. It’s so lovely. Abelard sits and looks at the device, hands folded on his lap. For a long time he doesn’t move. He’s like that. He’s in white, is sitting below a basement window, in a sunbeam. The ceiling is vaulted, has frescoes depicting all of our visits (there I am in the tub!), and his song becomes a choir. Abelard then lifts from the chair, floats above the device, and in a moment of clarity I know what it’s for, see the beauty in its design, and then Abelard becomes a dove, then a flock of doves, all flying wildly in the cathedral.

The day passes without too much else to relate. We have a brief conversation around noon when I ask Abelard if he’s happier these days. If, by finally acting, he feels a little more complete, or fulfilled. We both know the answer that we’ve begun to feel more and more awkward in each other’s presence that we haven’t a lot in common, and it’s almost embarrassing. The silences, the sighs.

Is this what you expected, everything you imagined it to be?

Can’t say, he says.

But you must have thought about it?

He gives me that look again, says Yes, I have.

So is it?

He doesn’t answer. He picks up the spray bottle, sets it down. Rearranges some rags, dusts a little, clears his throat. He sighs and puts his hands in his pockets, pulls out a small cloth and cleans his glasses. He sighs, won’t look me in the eye.

I don’t know why, I tell him, but for some reason I thought you’d be a better cook. Abelard, tell me, can you cook anything other than macaroni and cheese?

Abelard sighs one last time, makes a sound of frustration, stomps up the stairs. Do I hear him scream? I hear him leave the house. For supper he brings me canned ham and large bag of plain potato chips. In the evening its green tea and an awkward hug goodnight. Abelard, Abelard, such a creature of routine?.

Before my capture Abelard and I went a number of months without meeting, though one morning I did see him on television. It’s true. A reporter was talking about the better weather, the opening of the sidewalk cafes, and there he was, Abelard, in the background, reading a newspaper. I swear he glanced at the camera just before they cut away.

Does he plan that?

When he followed me and my driving instructor, could that simply have been coincidence?

Everyone had told me this, too. That after a while you’ll begin to have doubts, you’ll begin to question your kidnapper’s commitment to you. You will say to yourself: if he wants me so badly, then how come I’m still here? Things have changed. I’m no longer of interest. He’s found someone else.

It’s crazy.

When Abelard’s in bed, I escape. I unscrew the metal loop from the wall (was loose when I awoke this morning), reach the keys (they’re on the table), remove the collar from my neck, and wander about. It would be nice to see the sun, I think, but its night. Or the moon and the stars, then, except that it’s cloudy, raining. And maybe I’m thinking this just because I’m supposed to. Held captive for thirty days, what did you miss the most? Oh the sun and the stars, the birds singing, the wind in the trees. What I do is find a stool. I place it next to the table. I undress and perch myself on the stool and try to figure things out. My body is shivering with excitement, anticipating Abelard’s sudden arrival (though I know he’d do nothing; it’s all just fantasy), anticipating what I’m about to do. I stand, place one hand on a ceiling beam to steady myself, reach a foot out. It touches leather and my heart skips a beat. I balance on that foot and swing my weight, release the beam, and I’m standing in the Cockpit. Slowly I fall to my knees. I caress the straps, the metal buckles. I lay back, close my eyes, and moan.

Good God, I say to myself, what’s this all about? The air is cool, but there’s warmth in my thighs, between my legs. My heart is racing, racing. Abelard, I whisper, you’re creeping me out.

I ask him if he dreams. Around me the things of the basement take on odd, shifting shapes. I ask him what he desires most. Shadows of hammers, glint of teeth of hacksaws. Maybe this is all a dream of Abelard’s. My fingers trace the rim of the Plexiglas, and somewhere above me, up dusty stairs laden with mousetraps, is Abelard, asleep.

***

With the arrival of morning (my tenth or eleventh here), comes the memory of my mother, who’s telling me not to forget to say a prayer for Mr. Abelard. It’s a confusing time in my life. I’m kneeling at the bed, wearing a pyjama which is covered in either fish, or stars?

The man who came for dinner?

Yes, dear, there should be love for everyone.

But sometimes there isn’t?

Abelard is standing above me. Abelard is giving me that look again. It’s not the first time he’s seen me naked, certainly, but things have changed, and oh boy is this awkward. Say something, Abelard. I get up on my elbows and tell him the thing could use a little padding, because my neck and back are killing me. Hand me something, Abelard… Oh, Abelard, lighten up. I stand, steady myself, step on the stool then hop to the floor (the cement is cold!). While getting dressed I notice the pink and white imprint of a buckle on my bum. I massage it.

What to do?

Abelard’s jaw is clenched, and he sighs three or four times, then kneels before the wall, inserts rubber cement into the socket-thing where the screw-thing goes, and screws me back into the wall. Tells me not to move. I feel I’ve fucked up. I feel I want to cry.

Vigorously Abelard begins to clean the Cockpit, spraying and disinfecting and scrubbing and not even humming to himself as usual. Today all song has left Abelard. O misery, misery. Eventually he slams down the spray bottle, throws a rag at me, and storms back up the stairs.

Anger management, I shout, though I do spend the rest of the morning apologising. Can he hear me? I haven’t eaten. I imagine him with headphones on, something classical twinkling in his ears, sitting at a drafting table going over the blueprints for the device, saying uh-huh and hmm at lot. But it’s probably not the case. I think this is what people call sensory deprivation: I’m beginning to see things that aren’t really there. Bags of doughnuts, maybe. To tell the truth, captivity has been disappointing. You spend so much of your life thinking about it. For years Abelard lived in my closet, stood there at night watching over me, stood straight as a board staring at me. I knew he couldn’t leave the closet, unless I made some sort of mistake. I couldn’t talk to him, had to pretend like he wasn’t there, though when I got a little older I simply started closing the closet doors at night, telling myself (here’s logic again) that Abelard could only get me on the 200th time I forgot to close the doors, which would be years and years away?

Such childhood fantasies.

And my mother made me send Christmas cards to Mr. Abelard. And one Christmas morning he sat under the Christmas tree and handed out presents to everyone, but he messed everything up. We didn’t want to hurt his feelings, so we opened whatever gifts he handed out, and my mother got a laser gun, and I got an electric razor, and my father got pantyhose, and so on.

I scream his name and rattle the chain against the floor, the wall, but he doesn’t come down till noon, humming, cleaning his glasses.

I call him a stinking ape — missing meals has always made me cranky.

And I’m restless.

He feeds me the last of the stale doughnuts, saying he’ll get more this evening. I tell him, adjusting the chain around my neck so that I can swallow, that I prefer the jelly-filled ones. Yes, he says, they’re good like that, and there’s a hint of a smile on his face, which makes me wonder if he’s been keeping those for himself. His verbose mood continues when, while making a tour of the device (testing the Plexiglas walls, screwing this, gluing that), he tells me the long, boring history of torture devices shaped like musical instruments — oh no, his is not the first guitar! Though it’s an interesting enough selection, he says, muttering. Then the name Giovanni is heard, and certain dates. Torino, too. Is Abelard saying something in Latin? But times have changed, and mechanisms cannot be ignored. That is what we are, he says. Brilliant, a certain Livio in Sardinia, and his cave of lutes… bats, bats…by the sea?

Well, I’m not all that fascinated by it. My mind is elsewhere. Day of my capture, that’s what’s in my head. Recalling the dream I had that night, a dream with typical Abelard-imagery (I’ve had them all my life, it seems) involving a maze (this time an old house) and a high room with shifting floors. I have to get out of the house, but I’m running against the walls, and I’m bouncing back. Damn. The entire top of the house, the room I’m in, is bending, flexing, tilting, as if it’s the spring-held head of a jack-in-the-box. And there’s Abelard’s King Kong face in the windows…

Morning of my capture…

I wake up early with the feeling of dread, not because of the dream — I’ve had worse — but because I’m scheduled for minor dental surgery in the afternoon. Shut up, Abelard (he’s giving a short history of the barbed ukulele). So here I am on the bus. Sunny day. And here I am in the dentist’s waiting room, sitting quietly, thinking I’d rather be in school. And here I am being led into the office, and here’s the chair, and everything is gleamy and piercing. And here I am leaning back and taking a deep breath and here comes Dr. Thrill Drill himself, needle at the ready, How ya doin’, Doc? And hey, why you wearing that mask, Doc? And since when have you grown a foot taller, Doc? Is this the steady hand of an expert with twenty-two years of orthodontic experience? And why is the pretty nurse holding me down, Doc, strapping my arms to the armrests? Hey! And then the long needle sinks into my neck, my legs twitch, twitch, and behind the mask there’s a glint in the pale, amoral eyes of Dr. Abelard…

Now, the Great Nettle-Harp of Alexandria…

I swear escape is near!

***

Abelard tells me it’s been only a month, but I know he’s wrong, I know it’s been years. At times I think: this is all there has ever been. Nights like seasons. Abelard tells me he doesn’t want to hurt me, that he only wants to help me, that’s what it’s all for. Mostly I believe him. He whispers in my ear while I lay back, strapped in, the starry ceiling swirling. You can feel his wheezy breath on your cheek, sense the excitement in his voice (he’s changed so much). Then the device is activated. Then he places the headphones on me. And for a second his cool fingertips rest on my forehead.

It is the beginning of the second week, he says…

Really? That’s all?

Abelard sings incessantly, upstairs or downstairs, even when he’s outside, mowing the lawn, trimming the hedges. It’s spring. He sings while sewing another metal loop into my skin (my teeth clenched on a rag), sings while dabbing the blood. He tells me about his childhood, of sandy cliffs by an ocean and a plastic container full of white spiders. I would sit there, and the spiders would shiver in the palm of my hand. I would close my fist around them. And they would shiver.

Everything’s a work in progress, he tells me.

Two weeks of sleepless sleep. Oh Abelard, just give me some pills and let me rest. It’s never been done, he says. This is the hardest part. Oh Abelard…

The lights go out.

The first night nothing happened, so I lay there, in the dark, while Abelard replaced circuits, checked the outlets and wires and switches, saying he didn’t understand, he didn’t understand. After all the years of planning, dreaming, scheming. He left me there the whole night, strapped in.

But what’s it supposed to do? I asked in the morning, rubbing my eyes, stretching my neck.

What it’s supposed to do, he responded.

Abelard…

He whispers about his mother, how one morning she shaved off all of her golden hair, then went bald for years.

He whispers about the two girls who lived down the lane, how they’d meet in the woods.

He whispers until the headphones are placed, then nothing is heard. The second night it worked like a nightmare. Abelard wired me up and switched on the device and it felt as if I were no longer whole, as if I were a hive of electric ants. I screamed, I know I screamed, because my mouth was open, and in the morning my throat was raw. I had dreamed for hours, hours of being torn to shreds, dreams where every door I opened, every possible escape would lead to claws, teeth. That’s gets exhausting. At seven in the morning the device shut down. At seven it always shuts down.

I awoke from endless annihilation to the sound of the lawnmower.

When Abelard came I told him it wasn’t much fun.

But now it works like a charm, right?

Abelard clicks off the light, clicks on the device. He comes to me, as he has come to me every night now, for years and years, and whispers in my ear. He tells me to clear my head of all impure thoughts, of all expectations, of all memories, to be open to what will come, what should be. He puts his index finger on my forehead, says Here, I have drilled a hole right here, taps me, says imagine it. It all comes in through here. It’s like water flowing from a tap. His glasses reflect what little light there is, starlight, or twitching switchlight. He moves so slowly. My body is humming, and I feel mousepaws moving beneath my skin.

When I was a boy, Abelard says. When I was a boy?

The headphones are on.

He leans forward, gives me a kiss. He’s gotten better at it, though he still sticks his lips out too far. His hand rests on my forehead and I see him mouth the words “now you will dream,” or, “I love you.” But maybe I imagine that part. It’s too weird. Then everything comes alive and there’s a panic coursing through me. I don’t want to dream. I’d do anything not to dream. Last night I dreamed that one morning I awoke to find Abelard, not my mother, leaning over me. I dreamed that that was the day he captured me. And oh, Abelard, I didn’t smile for years after that, my family and friends had vanished, I was moved to a new school. It all came back after years of denial. Oh how I hated you. I remember crying in the bathroom, the door was locked, and you were telling me that my parents wanted me to be with you, that they’d planned to have another child anyway, that they’d be happier. But I was stubborn, I didn’t believe it. You laughed, you laughed…

You’re such a bastard.

Yes, and then I dreamed that one cool summer morning I sneaked out the back door, get on my red, dew-wet bicycle and pedalled for hours, the dawn sun at my back. I pedalled till I was beyond the suburbs, I knew what I was doing, I’ll find the highway, yes, I’ll ride the shoulder. Yes, so I’m pedalling and thinking of dogs and cats that have strayed, that have lost their way yet have found their way. My legs never weary. I hear the gravel crunching, the weeds whipping my pant-legs. When I see a dusty side-road I leave the highway shoulder and find myself surrounded by forest. I pedal the rutted lane, so much of the day has passed, the sun is falling, there are spikes of it flashing between the trees, and the forest is growing taller and taller around me. But this isn’t home. No, this is nothing like home. How could I have been so wrong? I should turn around now. With great effort I pedal up a high hill, and when I reach the top of the hill my chain snaps and I glide down the hill, the chain dragging along behind me. The chain drags along behind me and at the bottom the hill, lustrous in the dusk sun, there’s a meadow. And at the edge of the meadow, in black silhouette, there’s a man.

It was Abelard, of course. And I wanted to tell you this before I’m completely his, because there’s still something of me here. Maybe the last of it.

What will I dream tonight?

* * *

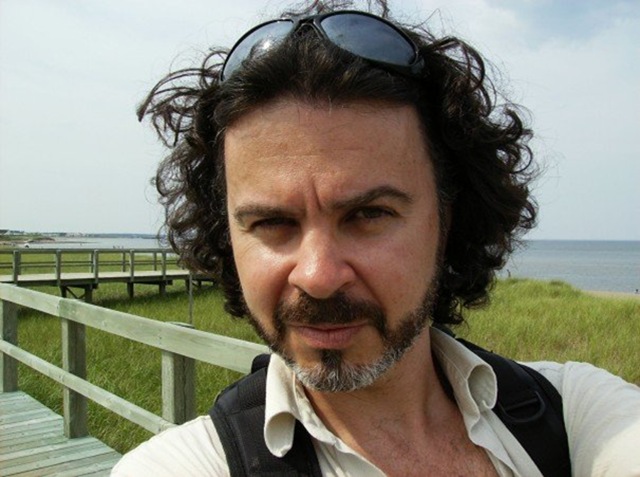

About the Author

Born in Moncton, New Brunswick, Lee D. Thompson’s short fiction has appeared in literary journals and anthologies across Canada. He has been a recipient of writing grants from the New Brunswick Arts Boards and the Canada Council for the Arts and is the founder and editor of the fiction journal Galleon.