On an early Friday morning in June of 1946, I started walking down to Mount Pleasant Cemetery with Sonny and Jimmy. My parents were still asleep and I knew my mother wouldn’t like to know her nine year old son was walking all the way down to the end of Seattle’s bus line. We walked fast, wanting to get far away from our homes, knowing that if we heard any of our parents calling us, we would just have to turn around. Sonny wore a pair of faded blue overalls over a tee shirt, while Jimmy wore his favorite green and white striped shirt and a pair of old jeans. A little round hole on his shirt revealed the puffy pink skin of his stomach. I can’t remember what I was wearing, but I’ll never forget what we saw that morning.

Jimmy still had a cold, sniffling and blowing his nose into a gray handkerchief he carried in his back pocket. Sonny kept pulling out his Navy pocket knife, opening and closing it and then dropping it back down in one of his huge overall pockets. We weren’t talking because we were all walking so fast. Soon we crossed Crockett Street and we knew then we were far enough away that we couldn’t hear our names being yelled from back porches. Jimmy, a little fat, held up his hand to stop us. He gripped his side and breathed hard. “Hey—you guys—” he said in his high pitched voice, “Let’s stop walking so fast.”

Sonny leaned over, picking up a dead maple twig from the grassy strip, got out his knife, opened it, and cut some bits off the skinny twig. I watched him for a second, then said, “Okay Jimmy — you let us know when you can walk four more blocks.”

Sonny just laughed. He was too big to be snotty; after all, he was one of our leaders. Jimmy’s face got a little red, but he followed us as we now walked at a slower pace until we reached a vacant lot next to the end of the bus line. The cemetery (our morning’s destination) was only one block away, but for some reason, I felt an urge to go into the vacant lot.

Jimmy was afraid to go in there because he had been stung by a bumblebee the last time he tried it. I didn’t care about bumblebees, I said. Sonny leaned against a slivery telephone pole, flicking small chips off an alder branch he picked up after he’d decimated the maple twig. Jimmy didn’t say anything, but the way he stood made me know he wanted to go down to the cemetery.

Then he whined, “Come on, Sam, let’s just go down to the graveyard.”

“What do you want to do, Sonny?” I asked.

Sonny folded up his knife, dropping it back down in his pocket. He had sharpened his long stick into a nice point and held it like a spear. “I’d like to go into the lot, Jimmy, and kill you a couple fat bees. What about it, Sam?”

“Sure,” I said, always ready to follow Sonny. After all, he was almost eleven and practically finished with fifth grade.

Sonny walked across the sidewalk and over a fringe of hard dirt to reach the vacant lot’s doorway — two tall alder saplings only eighteen inches apart. He was holding his spear against his chest upright as he squeezed through the alders. A second later I moved sideways through the trees with Jimmy so close behind me I could hear his teeth clattering. The lot’s narrow path wound down past high fragrant grasses, weeds, and wild blackberry bushes that brushed against my bare arm, causing a thin line of blood. Sonny didn’t get scratched once as the sun now shone through the screen of branches and leaves. We could hear a chorus of bees and blue bottle flies, believing those sounds proved Jimmy knew what he was talking about.

We struggled down this path for what seemed a long time until we finally came to a clearing. Sonny got there first and started yelling. Then I reached the clearing and sucked in such a deep breath, I got a pain in my side. When Jimmy arrived, he just screamed, turned around, and raced out of the lot. Sonny and I couldn’t move. We were frozen, our mouths wide open. Because just ten feet away from where we stood, a man dressed in a pair of navy blue slacks and white shirt lay on the ground. A hunting rifle extended from what used to be his right ear all the way down below his left knee, his left thumb still pressed against the rifle’s trigger. Most of his face was now red meat being feasted upon by ants, yellow jackets, and blue bottle flies. I was tongue tied for a second, but then blurted out, “I didn’t know yellowjackets – Sonny cried and kept saying “Jesus” over and over again. I didn’t cry, but felt fascinated by the sight of this prone man who had blown sixty percent of his head off.

I walked closer to the body and then knelt down beside it. I didn’t touch the man or move the rifle, which crossed his white shirt with its barrel end resting on his unblemished shaven chin. The rifle’s butt stretched over to some soft dirt a good eight inches away from the man’s pants leg. I stared at the red flesh covered by hordes of bugs undisturbed by my presence. I even noticed some of the man’s brain tucked under a cave of skull the big bullet missed. I felt myself wanting to touch that beige curled brain tissue and had even lifted up my hand when I heard Sonny yelling at me,

“Goddammit! Sam! Let’s get out of here.”

“You go ahead, Sonny. I want to look a little more.”

I heard Sonny swishing by the undergrowth on his way out of the lot, while I rose and walked around to the head of the man, taking in this picture: he lay with his legs straight and close together, like a soldier at attention, his rifle crossing his body diagonally. I understood what had happened: the man had pointed the rifle into his mouth, his thumb against the trigger and then he pushed it in—where it still was—the trigger tight against the blue metal, pushed there by a thumb now stiff. As I stood in my position, looking down on the remains of his face and his otherwise intact body, I wondered who he was and why he had killed himself.

As I continued staring, I remembered Slim Jenkins, a friend of my parents, who had just been released from a Veterans Hospital. He had sat at our kitchen table, full of the shakes, his hand almost couldn’t lift up his coffee cup. When I asked my mom about it later, she told me Slim survived three years of fighting in Europe, almost getting killed himself, but because Slim had seen so many terrible things, he still had the shakes a year later. So now here I was, a nine year old, seeing an awful thing. Would I get the shakes too?

With this fear I finally realized I was looking at a dead man whose head had been half-torn off by a bullet from a high caliber rifle. Then I turned away and ran. Out in the sunshine, Sonny leaned against a telephone pole carving a new stick with his jack knife.

“Where’s Jimmy?” I asked.

“Who knows? He’s probably back home. Say—what’s with you, Smitty? Looking so long at that dead meat! I was scared I’d puke in there.”

“I dunno Sonny. It was like I couldn’t move.”

Just then a huge empty #2 Seattle bus pulled up to the curb, its air brakes hissing as its double doors folded open. A tall bus driver slipped off his padded seat, using the large plastic steering wheel above his knees for support. He pulled off the chrome change container next to the fare box, gliding down black rubber stairs to reach the sidewalk. “Hi fellas,” he said in a jolly tone.

Sonny continued hacking at his stick when I almost yelled, “Hey—you better go into the lot and take a look.”

The bus driver’s lips pressed together as he looked down on us. “What’re you kids up to? Stealin’ transfers?”

“Naw,” Sonny said. “Close up the bus, if you want to, but you need to see what’s goin’ on in there. You’re the first adult we told.”

The driver walked back into the bus, picked up his black leather pouch, and took off all his transfers from its holder. He came back out, clutching his stuff, and then in an unfriendly tone, said, “Okay, I’ll take a look, but if you kids are messin’ with me, and if I ever see you down here again—then—”

That last part just trailed off as he walked into the lot. We were impressed that he knew how to enter between those two alder saplings and we guessed he probably went into the lot to pee or something. In a flash, he burst back by the little trees and he was shaking. His eyes opened so wide I thought they would fall down on the hot sidewalk. He dropped a nickel into a pay phone closeted next to Sonny’s telephone pole. Emerging from the booth after he made a short call, he breathlessly said, “You kids stay here ‘till the cops come. They’ll want to hear about what you saw.” Then after a couple breaths, he said, “For Chrissakes! His body’s warm.”

That was a real surprise. I was right next to him and I even sat down close to him, but I hadn’t known his body was still warm. I guess the bus driver must have touched his skin to know that fact. A few minutes later a patrol car with its siren blaring arrived and behind it a couple reporters in a beat up Model A coupe skidded to a stop next to the bus. The two policemen raced into the lot, but one reporter started asking me questions while the other one (a photographer) also ran into the lot.

“Okay kid,” the Seattle Times reporter began, “First tell me your name and address; then what you saw in the lot.”

The reporter leaning over me pressed his pencil so hard on his notebook, I thought its paper would tear. I told him everything I saw and when I finished, he walked over to the bus driver to grill him. For some reason, Sonny was left alone. When the cops came out of the lot, they also spent their attention on me before grilling Sonny. I was glad the cops asked Sonny questions because the reporter’s ignoring him might have made him feel bad. The photographer took a picture of both of us. And the other guy from the newspaper asked Sonny for his address.

The cops took us home in their patrol car and dropped me off in front of Benny’s Butcher Shop. My family lived in a large flat above the meat market and our front door bordered one of Benny’s display windows. This door opened to a long interior stairwell and I climbed it fast, wanting to get upstairs so I could eat my lunch. I wanted my mother to make me about three baloney sandwiches with a tall glass of creamy milk. As I sat at the kitchen table hunched over my food, mom sat next to me watching me eat. She must have noticed a strange glint in my eyes. She could always see past my contrived looks and gently dig out the truth. “Okay Sammy, what’s going on? Where were you this morning?

If I told mom where I really had been, she would know I had gone at least two miles away from home. I drank my milk slowly to delay her grilling. She cocked her head to one side, burrowing into me with her light brown eyes. “You were all the way down to Mount Pleasant Cemetery weren’t you? Tell the truth, Sammy!”

As I sat on the hard wooden chair, clutching my jelly glass, I wished my mother couldn’t read my mind, but just before she named the cemetery I had thought about it, realizing we never had reached it to play hide and seek behind gravestones and monuments. I sighed before swallowing down the last drops of milk. “Well, we almost got to the graveyard,” I said. Then I added, “You know what? I’m gonna be in tomorrow’s newspaper.”

I knew I’d said the wrong thing when my mother’s glasses fell off her nose to bang on the kitchen table. She was breathing hard and when she caught her breath, she asked, “What? What happened?”

When I finished telling mom what happened, I noticed the sad expression on her face. She seemed to be suspended, not knowing what to say. Finally I broke her spell, asking,

“What’s the matter, mom?”

“Oh—I guess I feel bad because you had to see that—a dead man—gruesomely killed.”

“Will I get the shakes? Like Slim?”

Mom took my hand in both of hers, saying, “No Sammy, you won’t get the shakes. Slim was in the war for three years. He almost got killed a couple times. Say—listen. It’s a beautiful day. Why don’t you take Spotty for a walk?”

Spotty was my dog, a little bigger than a cocker spaniel and she was all golden brown except for a diamond shaped white spot on top of her head. She was half spitz and half cocker and loved to go outside with me. She must have understood what my mom said because she was sitting on the kitchen floor with her tail banging the linoleum like a small hammer.

I got up from the table, kissing mom on her forehead before racing out the back door followed by Spotty flying down our long wooden staircase. Our backyard was paradise with its eight small sheds each with separate doors and beyond these sheds an old fashioned barn. This stuff had been used by the butcher shop which had been in operation then for over fifty years. My friends and I played all kinds games around the sheds. We could hide in them fight in them, scream in them if we were being ‘tortured’ by ‘Nazi soldiers.’

Now as Spotty and I walked by them, I suddenly realized what these sheds had been used for: killing. Sticking pigs, wringing the necks of chickens, geese, turkeys; or banging the life out of wriggling rabbits. They were slaughter houses. I’d never thought about this before I saw the exposed flesh of that dead man in the vacant lot.

The next day I had my five minutes of fame with the pictures of me, Sonny and the bus driver in the newspaper. The story explained that the dead man had been a deaf mute whose depression caused him to kill himself. I had to ask my mom to explain what “deaf mute” and “depression” meant. After she finished explaining, I had to go outside and be by myself, alone with Spotty.

The sheds’ dark brown wood looked evil and sinister. I wondered if I would ever be able to play in them again. Then I ran up to the sidewalk and without thinking walked into the butcher shop where pounds of red meat were displayed in neat folds, the white fat perfectly trimmed above the shiny red muscle of cattle and lambs. The butcher was in the back room about to bring out another tray loaded down with meat: slices of steaks and chops and he smiled when he saw me, but then I felt my stomach pulling down and ran out out of the shop. Before I could reach the end of our building I fell on my knees, puking until I could feel my body shaking and shaking as tears rolled down my cheeks and Spotty sat, looking puzzled as I curled up into a wailing ball. Ron Ballard is a published novelist and poet. His novel Brilliant Corners is available at Kindle, Nook, IPad, etc. He has four children and four grandchildren. Ron and his wife live in Hagerstown, Maryland. He is a gourmet cook and enjoys hiking the C&O Canal Towpath.

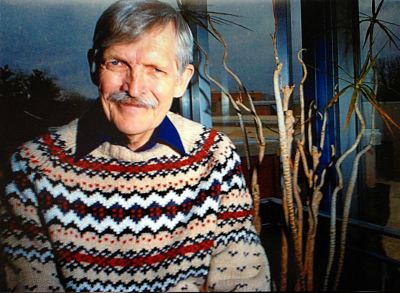

Ron Ballard is a published novelist and poet. His novel Brilliant Corners is available at Kindle, Nook, IPad, etc. He has four children and four grandchildren. Ron and his wife live in Hagerstown, Maryland. He is a gourmet cook and enjoys hiking the C&O Canal Towpath.