We met the same way we parted, Vincent and I: he in front of the camera and I behind it, looking at him, admiring him, appraising him. Trying to understand what roiled beneath his perfect skin.

It was he who, to my dismal surprise, approached me after the shoot. He said my name as a question. Evan Walker? The way he has never stopped saying it as a question; questioning my being. But how had he known the correct question to ask? Who had told him? I wore a name tag.

And you are? I had asked.

The model, he had said.

This was the first laughter we shared.

He asked if I would like to go for drinks sometime later in the week. Maybe catch a movie. He said this – catch a movie – like he was in one. No real boys speak this way. And he never was entirely real, his body always glistening with the faint ghost of silver gelatin: halfway in and out of himself; halfway photograph and halfway not quite man, halfway myth, Adonis.

(How can I explain the way that, now, I have come to avoid the magazine rack when I go to buy a pack of cigarettes? Once upon a time, I flipped through every one of them to just maybe catch a glimpse of him. How can I explain the way I separate the fashion section from the newspaper every Sunday morning, when once I went straight to it, looking for him? Routines that replace routines. The grinding of teeth during orgasm, now just the grinding of teeth.)

Before long, it seemed, we lived together. Though I kept my own apartment in Echo Park, it slowly became nothing more than my studio. I turned the kitchen into a makeshift darkroom, replaced the bed with flat files. I kept a cot folded up on the floor. Vincent began to pay the rent on the place because it held a practical use for him, too: it was a place to hide me when his family came around.

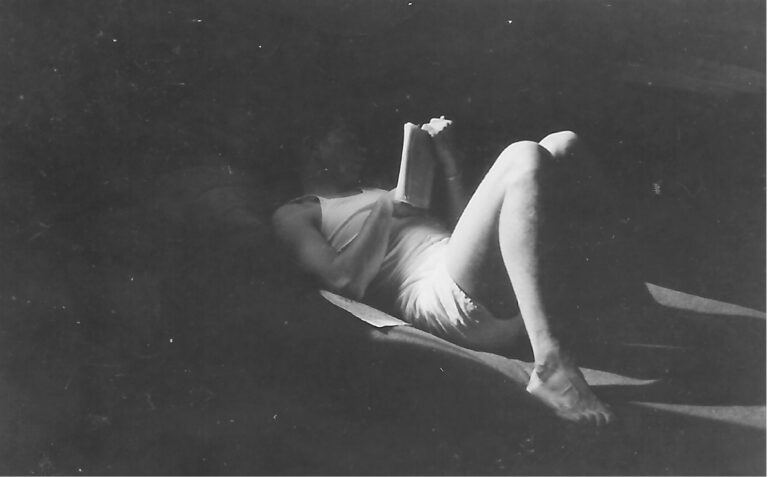

But we had made this place entirely our own, the place where this photograph was made: his mother’s cabana in Malibu, desecrating the playhouse of his Catholic family with weekends of boozing and sex. The weekends that always smacked of without-me-you-are-nothing, an unspoken sentiment, apparent only in moments of purchase – always his credit card, his cash, handed to the salesman in the liquor store, the server at the restaurant with tables on the beach – for which I forgave him because without him I was nothing: An artist, fledgling, a man chasing moments with an antiquarian contraption. While he was everything the American man was meant to be, even in his foreignness, his Italianisms: of money, of beauty (they call it handsome) and charm; of learned table manners, of private school education, and the Ivy League; of varsity, of biceps in Polo shirts, and stubble that could never be mistaken for bumliness.

Perhaps the only thing foreign about this foreigner was me – was his sexual predilection.

What he called his need, his need for me, which I now discovered was no need at all, but disposable in exchange for what the blonde girl offered.

At first he simply says, I met a girl. Offhand, the way you tell someone you met someone, not the way you tell your mother you met a girl.

Who’s that? I ask.

He explains, slowly bringing her into clearer and clearer focus, out of darkness.

She is the daughter of a news network mogul, a child practically born for the expenditure of money. She is the thing Hollywood craves; a nobody, already halfway up the ladder of fame.

What’s her name?

He never says.

It is unclear, at first, why he is even telling me about her, beyond novelty. The way he makes it sound, she is the novelty kind of person.

He says: Blond hair and blue eyes.

I do not quite register the connection to my own blond hair, receding, my own blue eyes, paling. Not then in that moment. (The connection comes later, as I puzzle over her – the idea of her – in the way only jilted lovers do.)

Anyway, what about her?

I’m in love with her, he says. I’m going to be with her.

I am too startled by his directness to muster anything other than a feeble question: Why?

She told me something the other day, he says, the strangest thing: she said she feels just like Naomi Watts, when she lights her cigarette off the burner of the kitchen stove at the beginning of that movie, Funny Games. It’s all in the hand, she told me, the way Naomi holds her hair to one side with her hand like that. How she does it, you know? Leaning into the gas flame.

This is his defense. He tells it to me exactly like this, as he sits reading in the low light.

Bad for your eyes, I murmur.

He continues to read. What book, I can’t see. He never turns the page, only directs his gaze there, at the words, or the spaces in between them, as he speaks quietly, persistently, of this girl and why he is leaving to be with her. Emphasizing the simplicity of the logic behind his actions: the way this girl tells him she feels on dreary afternoons – and the promise of what more she might tell him – that she feels like Naomi Watts in a movie that we, Vincent and I, had seen together in the theaters three years before: the movie we caught. (The second one, the English one. The shot for shot remake by the very same director as the original. The duplicate. The one with Naomi Watts.)

I even remember that Vincent had not been particularly moved by Watts’s performance. Leaving the theater, the sunset over Santa Monica, we had joked about the killers in the film, the young men in golf whites, and our shared desire for the one with the open face. How funny it was to feel attracted to a killer, maybe not even the actor who played him, exactly: it was not Michael Pitt, but his character that had excited me. Murderous and performative, unreal and unflinching, as only a model can be. A model like Michael Pitt. A model like Vincent.

I fiddle with the camera settings, eyeing Vincent through the viewfinder, afraid to look at him straight on, afraid to fully come into the room.

Well, does she look like Naomi Watts? I ask, squinting at him through the camera.

No, he says, she doesn’t look like Naomi Watts.

And I get the impression that maybe this makes her fantasy all the more intriguing.

Only she doesn’t, I say.

Doesn’t what?

Come to think of it, she doesn’t hold her hair back. Or light her cigarette off the stove. It’s with a lighter. From the purse. Okay?

He says nothing, considers the page, makes no sign of attempting to remember the scene. Though who knows what goes on in his head.

Believe what you like, his expression says, try to fight this. You can’t.

Okay? It isn’t even like that at all. She’s standing over the sink, anyway, not the stove. First of all, there’s that. So you see? It couldn’t be the way you said. Not even in a different part of the movie. In fact, she takes her hair out just before the cigarette part.

Evan.

She even puts it out in the sink. The cigarette? She puts it out in the sink. I don’t think you can even see the stove in the shot.

Evan. Stop it. No one likes you when you’re like this.

When I’m right?

When you’re difficult. You’re being difficult. And here I’m trying to make this easy. I’m being reasonable. Can’t you see I’m trying to be reasonable? Simple?

But it isn’t, I said – meaning simple, but I pivot, return – off the stove. It’s with a lighter. Just after the boy leaves with the eggs.

So you’re a big movie buff now? Is that it?

No. I just remember. Better than this girl of yours. I’m just pointing out that she didn’t remember the shot right.

You’re being argumentative, is what.

This is true, of course.

You haven’t said anything about you, he says. Why haven’t you?

I continue watching through the viewfinder. A long moment, silence.

You’re being eerie, Evan. Say something.

And what has he said? Yes, that he is leaving, that it is to be with a woman, but what, really, has he said? Empty words. Nothing. What could I say, now, in response to nothing?

I don’t know, I say. I’m hurt. I feel pain and you forget it. You forget that I feel pain.

Maybe feeling forgotten is beyond the grasp of someone who has been so immortalized, photographed, and reproduced. Maybe he actually cannot understand.

So, it isn’t even that you loved me?

The past tense, so soon?

Oh, Vincent, it’s that I feel love and pain, I feel them both. Don’t you know someone can feel both things? Can feel two things? Don’t you know that about me, at least? Don’t you know anything?

Here, he raises himself, on buckskin elbows, on the daybed. Still, he does not lift his eyes from the page. It is merely an adjustment, a shift of weight towards comfort.

I know that I feel two loves, he says. Aren’t those two things? Separate loves? The love I feel for you and the love I feel for her. There you go – two things.

The same thing split, I counter, though this is rash, an argument to avoid the conversation. Besides, I’m not sure even I know what I’m saying, and immediately fear that Vincent will snatch at this misstep. In an act of mercy – perhaps his last mercy toward me, and too late, anyway – he does not allow us to be diverted like that.

No, Evan. Two things. I feel them both, but one stronger. So. And for her.

When had this relationship developed, right beside me, yet out of sight? I tried to remember nights he had not returned to the apartment, days he had gone to work too early. But it was nothing so corrupt. Only his regular visits to the country club for his weekly tennis match.

Where did you meet her? I ask.

On the courts.

Tennis courts; country club. His club, I never went. Couldn’t be seen there. Everyone knew him, knew his parents. A body not to be seen beside another body, in any state of contact, even implicit. But she, her body, that was acceptable: in tandem motion with his, across the net, coming towards the net, shaking hands on a good match, the moving together, partnered in doubles. I imagined this. How else could friendships develop on the courts, other than partnering in doubles? The score is sometimes called love.

Her novelty was in her tennis whites, her earrings, her age. Young. Twenty-four. (My own assumption – Vincent said only, Ah, younger than me and you, so I placed her at about five years behind.) Twenty-four and not yet married off. Thirty next month and not yet married off. That was her and that was him. Married off was the trickery of the royal system they lived in.

I imagined her moving, her tennis skirt, and her legs shining with sweat, the curve of a delicate gold necklace echoing the curve of her tank top, clingy to the breasts, like the hair stretched across her scalp, a disposition imprinted through a childhood of ballet lessons. I imagined she was taller than I was, more athletic, less encumbered by life. Did she look in the mirror, at herself, naked on tiptoes, and appraise the body? I did this, doing so with two sets of eyes: my own and his.

Have you slept with her yet? I ask.

Evan.

No, I just mean how far has this gone yet? I just want to know if it’s like that or like this, all the way gone or you’re just thinking about it.

I am leaving, he says. I am going to be with her.

But are you with her now? Have you slept with her yet?

Does it make a difference?

If it’s bad, it does. (My attempt at some kind of humor, some kind of insult, some kind of drowning clutch.)

You know, he says to the page before him, you know that love isn’t all sex. With you, though, it always is. It’s always sex.

You love my body, my body. You tell me you love my body, but do you love me?

Of course I do, I say.

Well if you did –

Which I do.

– you would know it wasn’t all about sex. Whether I’ve slept with her or not, that it isn’t the deciding factor.

But if it isn’t what you like, if you sleep with her and it isn’t what you want.

I want her, he says, and I feel a harsh sickness turning over in my stomach. All of her. In a wholistic way. You, you’ve always been addled, sex-crazy. Crazy. Insatiable. Wanting, taking, needing. I get tired, Evan. (Here, he closes his eyes, still holding the book up in front of his face.) What do you have for yourself I haven’t given you? What haven’t you taken?

And the problem is, it is true. He has spent the last three years leading up to this, making sure that, when the moment came – and here it is – when the moment came and he said these words, they would be true. But I had taken nothing. He had given it all to me. He had disguised his purchase of power as generosity and now I was indebted, the owned and disowned.

But you saved me, I say.

And now, he says, I am the one who needs to be saved.

And still he reads, or refuses to lift his eyes from the page. And I watch him, through the camera lens.

He wears only a tank top, thin and sweat stained, and boxer shorts, his biceps and thighs shimmering with a coat of sweat in that slanted light through the open doorway. A wife beater, I’ve heard them called. Reprehensible name, and now a picture comes to mind: him hitting her. He has a tattoo, on his chest, above his heart, and it creeps from beneath the undershirt. (I had always liked to consider it my mark on his skin, though it had nothing to do with me, had existed there long before I had known him, and was something the makeup people were always covering up for photoshoots, like an unwanted blemish. This I learned working on fashion shoots, getting to know Vincent: some blemishes were desired, others covered up. The tattoo was nothing to do with me; the face of Marylin Monroe.)

Saved from what? From me? I ask, but I know. From himself. She would save him from himself.

Don’t make me say something I don’t mean, he says.

I can’t even make you love me, I say, let alone say a word.

But aren’t I? Aren’t I trying to make him speak to me, instead of through me?

Don’t make me say I hate you, is what I mean.

Well, you don’t, I say.

In this is confidence, because I know it to be true. The last thing I know to be true. He does not hate me: he hates what I make true about himself. His need. And I understand that she offers him a fiction.

And here is the moment; my chance to steal him one last time for myself. I do not say, Look at me, or, Look over here: I act with quickness and a violence.

I depress the button on the camera with the last of my strength, with a shaking forefinger that once had traced lines on his body. The small explosion – the crackling; the sound possibly mistakable for a gunshot, or for the crumpling of a mechanical heart – that gets him to look at me.

But before he could speak, I said, Enough. That alone will be enough.

I meant this to hurt him. I meant this to mean, Now that I have this, I don’t need you, either; I can take you with me, like this.

But even that last stolen moment was too much need, and he knew it before I did, and returned his eyes to the pages of the book as I walked out of the open doorway onto the sand.

I went toward the waves, the camera slung over my shoulder, past the few people watching the sunset, and I tried to remember who had opened the door, thinking, He or I? Who had left it open?